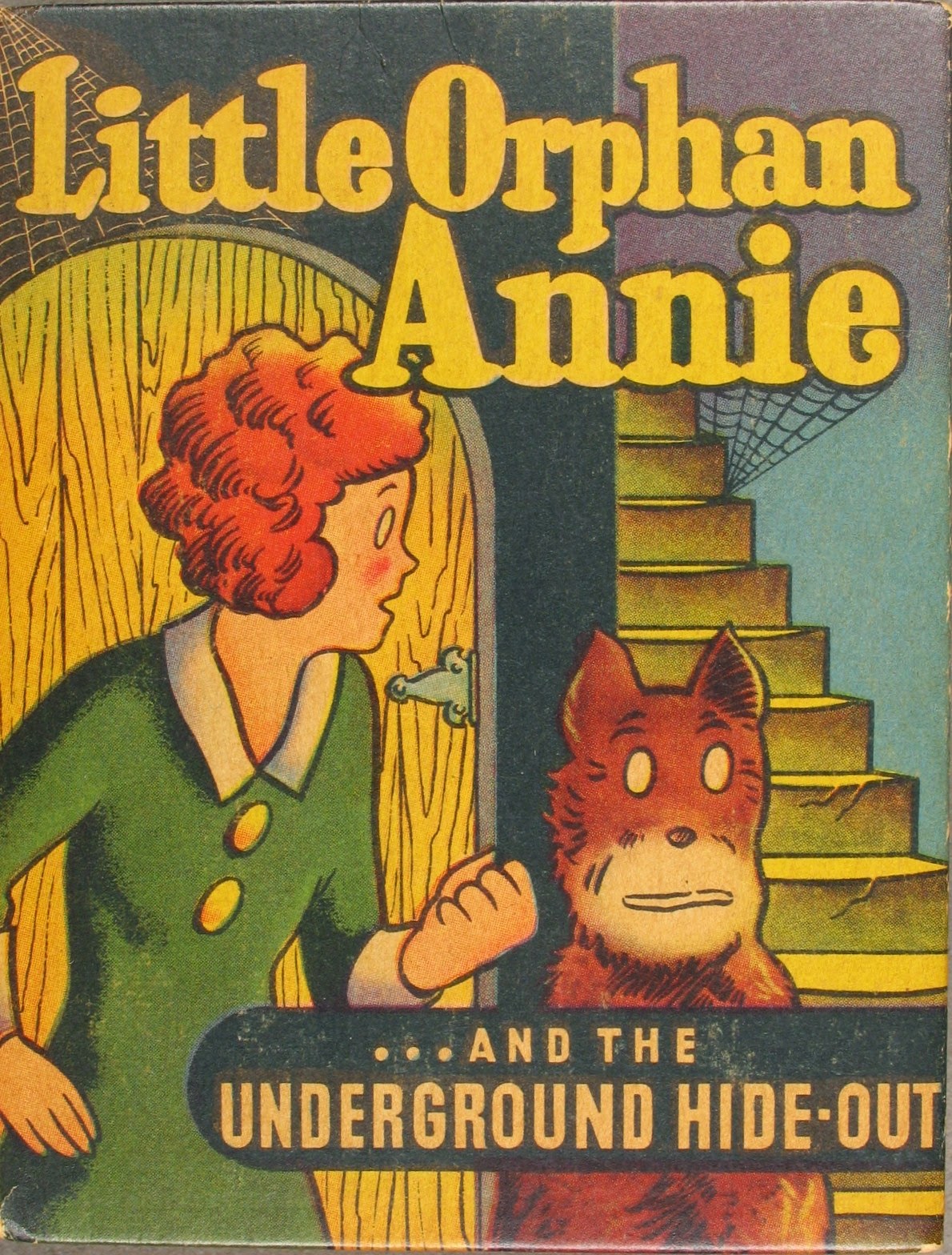

The V&A has asked me to transfer myself from social to art history. Talk was about the eye that built THE RAKOFF COLLECTION. Here is what I think as an exceptional cover. Inevitably I will talk about Lee Falk

Thursday, 9 October 2014

V&A Confessions of a Collector

Confessions of a Collector –

misdemeanours of a comic book addiction

A blog serialising the memoirs of Ian Rakoff,

screenwriter, film editor and obsessive comic book collector. Ian grew up in

the 1940s and 50s under apartheid in South Africa where he began collecting

comic books. Forced to give up his childhood collection, Ian then began

collecting again years later following a move to England. His vast collection

is now housed at the V&A’s National Art Library.

Read about the creation of this epic collection

on the V&A blog:

Idea for a sci fi novel

WHITEWASH

By

Ian Rakoff

Prologue

‘Civilization

was rotting on the vine and barbarism was spreading. Nation America was almost

obliterated in its attempt at world dominance. China and Russia nearly

annihilated each other but came back from the brink, shadows of their former

selves. Most Nations and continents lost all moral fibre and regressed to the darkness.

The

only beneficiaries of the worldwide disintegration were the accountancy firms.

Where the lawyers failed, the accountants prevailed.

Entering

the 4th Millennium everything was falling apart and no one seemed to

care a damn. Except for Lady Steingarten who was convinced she knew how to

forestall the rise of barbarism.

Unfortunately

she was dead.’

An

extract taken from a social history by the accountant C. Silverfish, appointed

chronicler of the era.

Chapter one BACK FROM THE DEAD

A couple of levels underneath

the ruins of the British Museum two ebony hued behavioural scientists patrolled

the corridors of a subterranean complex of the Steingarten Foundation. The

scientists ticked off their charts and dimmed the lighting, initiating the evening,

and discarded their surgical masks. Both women looked younger than their years.

A primary benefit of working for the Behavioural Department of the Steingarten

Foundation was a prolonged lifespan. Enclosed by research specimens, the scientists’

biggest fear was a power failure which unlocked the cages. On the last failure there

was barely time to escape.

The hum of the air

conditioners changed phase but the usual evening calm of the nocturnal mammals was

absent. Unsheathing sedation weapons the two scientists raised their torches

and scanned the banks of cages. They found nothing untoward, but the agitation

in the cages continued. Something was

setting the animals off. Something neither scientist could see.

A sound drew their

attention. The central lift shaft had been activated, yet no visitor’s pass had

been sanctioned. The one person with the authority to override the access

system was Lady Steingarten who was last seen twenty years ago. The inquest

recorded her as missing presumed dead.

The employees in the

complex were not unaware of the illegality of what they were involved in but

they were highly paid and rewarded with guaranteed body refurbishments. Employees

who asked unnecessary questions disappeared.

In an adjacent room

with a low ceiling and a putrid smell, the ground sloped towards a pool surrounded

by rotted carcasses from experiments gone wrong. A scientist recognised a pair

of spectacles on the ground and kicked them into the turbid water. She hurried

out feeling sick.

A few nights previously,

something or someone was heard rattling cages. On the surveillance disc covering

a walkway between the feline cages were splotches of heat flares. Both

scientists had a suspicion but took it no further. Contrary to Foundation

procedure they had destroyed the relevant recording.

The animals in the

cages fell silent. The lift doors slid apart and the imposing frame of Lady Victoria

Steingarten silhouetted in a light pulsating behind her, stood with an unlit

cigar in her mouth. The scientists exchanged a look which said it all. Their

Director was back from the dead. The scientists stepped aside and followed her.

It was as if she had never been away, and what had passed a couple of decades back

seemed like yesterday.

The animals pressed

against their bars as Lady Steingarten swept past; a large bulk but light on

her feet. The two scientists watched as she snapped open locks and released the

deadliest of enemies.

Lady Steingarten walked

away pulling on a pair of pink surgical gloves, followed by a black panther. As

it brushed against her thigh Lady Steingarten stroked its head. The animal

purred as any loving domestic pet might.

*

In a cavernous emporium

tiers of seats were packed. Academics, artists of various disciplines and bureaucrats

waited patiently. All were drawn from the staff working on the social engineering

project which incorporated The History of

Slavery Unit, The Department of Neuroscience

& Behaviourism and The Institute

of Human Conditioning. They were all funded by the Steingarten Foundation.

Not within living

memory (which for some was a particularly long time) had such a meeting convened.

After years of waiting Professor Mogadishu, the albino from East Africa, had

the temerity to try and pick up the reins relinquished by the assumed death of

Steingarten, and called the meeting.

With the imminent collapse of civilization,

Mogadishu thought his time had come. He had it all mapped out and had devised a

sensational entrance.

Charlie Silverfish,

accountant, was not happy. The demise of Victoria Steingarten had been a major

blow in his otherwise lacklustre life, and the likelihood of her replacement by

Mogadishu made him want to puke. To say he disliked the preening albino and his

butch skivvy with huge balls was an understatement. On the few occasions they’d

met since Lady Steingarten’s demise, the Professor had demeaned Charlie publicly.

When Charlie had been with Steingarten nobody would have dared to be

disparaging to him. With her he had been somebody. He vowed to some god he’d

never believed in that if she came back from the dead she would not be disappointed

in him

Only Steingarten could rescue

Charlie Silverfish from his appointment as accountant for the ailing UN.alliance.com

– the last major international complex left standing in Manhattan. The accountancy

complex was surrounded by razor wire, and protected by a detachment of overmedicated

armed guards. Charlie didn’t want to return to UN.alliance.com – but he had

nowhere else to go.

There were no clues as

to who was responsible for her death. Nobody had gloated over her

disappearance. No organization had claimed responsibility. There were no

apparent beneficiaries. Charlie had investigated thoroughly.

In the dim light the arrival

of Mogadishu took a moment to register. With an ear piercing brass fanfare and

a blaze of light shimmering across his albino features, Mogadishu’s entrance

was spectacular. The auditorium shook with the vibration of drums. Sitting on an

air-driven ivory chair he soared above the audience. The muscular Nubian,

Charlemagne, was perched on a platform on the back of the chair wearing only a

broad-brimmed cowboy hat and a skimpy jerkin studded with Strasbourg rhinestones

and buckskin fringes.

The drumbeats receded

and hovering to a standstill Mogadishu cleared his throat as a megaphone stopped

in midair in front of his face.

Before Mogadishu could speak, a piercing

whistle jarred him and the megaphone was whisked away as if by unseen hands.

The Nubian gave an involuntary shudder, raised his binoculars and scanned the

darkness until coming to rest on a sliver of light pointing to a corner of the

emporium. Charlemagne hissed with incredulity, ‘Steingarten is not dead!’

Charlie watched the megaphone sweeping away

and smiled. Across the auditorium on the edge of shadow a figure slid into a

beam of light. It was Steingarten’s unmistakeable shape. Charlie raised his

hand and wiggled his fingers till his rings caught the light. Steingarten saw

the glitter of his rings and knew them for what they were but displayed no hint

of recognition. That didn’t worry Charlie. He was euphoric, she was alive and

his life would not be the same again. That went for everyone else, unless she

was assassinated within the next few minutes.

The Professor and the

Nubian drifted towards Lady Steingarten, slicing through the shifting beams of

light and hugging the shadows as they floated to floor level. The market value

of an albino was immeasurable and Mogadishu was painfully aware of the value of

his parts. His balls were worth twice the price of a rhinoceros horn and a

couple of elephant tusks.

‘What should I do?’ Mogadishu

whispered. The Nubian said he had no idea, ‘and I’ve just spotted Silverfish,’ the

Nubian fumed dropping his binoculars. Too late he tried to retrieve them. They

floated away and the ivory chair reached floor level. The Professor groaned, as

he saw Steingarten’s fleshy lips sucking an unlit cigar clenched between tobacco-stained

teeth. She was gross, but then he was hardly a pretty picture himself.

Steingarten jerked the

Professor out of his chair and with a backhand swipe knocked Charlemagne off

his perch. She heaved her bulk onto the chair and ascended, putting on dark

glasses as light focused on her. With her elbows on her knees and her hands

clasped, she leant forward with a cluster of microphones hovering over her. Her

sonorous laugh reverberated. She was like an old friend who had returned as if

she had never been away. The years had not depleted her uncanny ability to

exude warmth. She tore off the arm of the upholstered ivory chair and flung it aside

saying what a cheap piece of shit it was.

Lady Steingarten purred,

emulating her feline companions gathering in the shadows out of sight waiting

for her to summon them. She smiled at her audience and spread her arms apart as

if she was about to hug everyone. ‘Colleagues and old friends,’ she began with

a catlike lilt; the artist of persuasion and the master of conviviality. Her

words were velvet; a mother comforting her babies. A switch was adjusted and her tone altered.

She segued into something more risqué, more edgy. She reminded the audience

that her resurrection was no excuse for complacency. Comfort was not in her

scheme of things. There was not enough time left for syrup. The eternal

iconoclast was warming up.

Civilization might be on

its uppers but Lady Steingarten would go to her grave driving humanity along

the path to redemption, which was what she was leading them towards to save

them from themselves. Her pedagogy was raising the dead. Steingarten had

absented herself, she explained, because she had been researching how to

penetrate the past to salvage the present. A pivotal moment in the past had to

be un-warped and reconstructed.

Lady Steingarten pronounced

the refutation of the 11th commandment, thereby advocating time

travel, condemned for so long by banned religions and governments with equal

fervour. Combined with social engineering it would have made anyone else a

target. Steingarten, however, with the following she had generated over many life

spans was unassailable. Only Mogadishu thought otherwise.

*

Steingarten’s

experimentation had met with success and that was why she had returned to

society and the Foundation. The historical rewrite was poised to begin.

A concave unsupported

screen flickered to life engulfing the auditorium. Whether the images were

moving or the audience rotating could not be discerned. The picture emerging was

too textured and too all encompassing to be a cinematic confection. A

stagecoach (circa mid 19th century) rattled across a barren cacti

dotted landscape. A couple in the audience, flicked by the lash of the driver’s

whip recoiled and glanced in wonderment at Lady Steingarten, but could not see

her. Only a hint of her flabby jowls slipped in and out of view. She shifted

into shadow and left the audience with the cloying taste of the dust churned

up. The authenticity was irrefutable. It was a thorough achievement, though not

entirely according to her instructions. She felt her heart skip a beat;

something was amiss. She’d factored in every probability but there had been a

possibility of feedback when timelines abutted. This was such a fanciful notion

that Steingarten had given it not the slightest credibility. It was too frighteningly

in the realm of the unknown and she, an avowed pragmatist had left no loopholes

for magic or mysticism. Why should she? She had no intention of going as far

back as the Dark Ages, or the medieval. So where did her feeling of apprehension

stem from?

The arid prairie

receded and the stagecoach entered a barren dustbowl. A western town filled the

ceiling and wall areas. The constraint of screens vanished. It was the theatre

in the round, writ large, writ real. The blistering heat, the dust and the reek

of horse manure convinced the audience that what was unfolding was an actual step

into the past. A time-shift had been generated; a certifiable crime and the

hallmark of madness. Everyone present was corralled, caught and trapped in

Steingarten’s mind.

Whether the audience

was immobilized by fear or mesmerised by Steingarten was impossible to gauge. No

one in the audience dared move. Tumbleweeds blew across a gravel surface. The

dissipating dust revealed that figures clothed from frontier days were cardboard

cut-outs. A storefront fell over exposing support struts – mere facades.

Rearing coach horses stayed up, hooves in midair; two dimensional artifices

like everything else.

Lady Steingarten, breathing

heavily, tilted the chair to make her features less visible and eased back into

darkness. She tried to halt the ongoing process but nothing responded. She

could not switch off or disconnect anything. It was beyond her control.

Nonetheless, she spoke

calmly, reassuringly as if nothing was amiss. ‘The town of Harmony disappeared

from the map and was called fiction,’ she elucidated and continued, ‘the

elements have been set into play and the participants in place.’

Steingarten recognised the

characters in the cut-outs, historical figures she had incorporated from

different environments and different time slots. She had not despatched anyone

to Harmony which was a fabrication, a sort of wishful thinking. Her team had

researched Harmony but glitches intruded and the territory was deemed unsafe,

uncontrollable, if it did exist. So she’d steered well clear, or so she’d

thought.

Lady Steingarten shut

her eyes but a gasp from the audience made her look. The central cut-out figure

had morphed into life and was staring at Steingarten. A hand was raised and

pointed at her. It held a palm sized derringer. As the finger squeezed the

trigger, a hand in a sleeve with silver studs and buckskin fringes, reached across

and jerked a swaying cord. A bullet pierced the screen as the cord dropped obliterating

the Western scene. Steingarten blanched as she felt the bullet whiz by her cheek.

Wraithlike the images dissipated

in the rising of the auditorium lights. Unattended trays of champagne and

canapés floated up the aisles. People grabbed at the refreshments ravenously as

if fending off what they had witnessed, and what might be happening outside

beyond the subterranean bulwarks and caissons protecting the Foundation, and

the huge earth mound covering everything.

The Harmony backdrop

was supposed to switch to the assassination of the anti-slavery President. Now

the question was; had the President been prematurely assassinated? Her team was

still honing their observational skills into the past but the indications had

suggested that it would be fatal to delay intervention.

Steingarten was

unnerved. She had spent far too many years alone. No one understood her except Charlie

Silverfish who had the knack of connecting with her innermost sensibilities.

During her prolonged absence she had followed his activities, powerless to stop

his fall from grace without exposing herself. It would have been premature to

break the 11th commandment earlier.

Then her researches indicated

that something was moving faster in a timeline beyond her observational field.

She could delay no longer, especially with that ambitious turd the albino

getting uncomfortably closer to the heart of the matter.

Mogadishu brushed past

Steingarten as she vacated the ivory chair. He directed the Nubian clutching the

retrieved armrest. First he wanted it higher, then lower. He was too nonplussed

to know what he wanted. Steingarten coming back to life had thrown him.

Charlemagne squeezed Mogadishu’s arm. That gentle touch was as much as he was permitted

in public. Mogadishu nodded and wriggled back into the ivory chair as it soared

up.

Steingarten eased Charlie

into a dimly lit corner. She glanced around to ensure they were alone. She

needn’t have bothered; no one dared to get involved or cared a hoot about Charlie

Silverfish. A few delegates edged away cautiously.

‘What!’ Steingarten exclaimed and pushed Charlie. He

cringed and apologised, though he didn’t know how he’d offended her. She jerked

him onto his feet. He fell into her arms blathering that it was so good she was

back. He was weeping unashamedly. She was touched. It made her smile. Once

again he was offering himself to her, completely. He ached with the pain of

missing her every moment of every day since she got blown up on the riverboat. He

nuzzled into her bosom and arm in arm they ambled into the stage footlights.

A bank of microphones glided

around Lady Steingarten as she spoke: ‘What you witnessed was no contrivance.’ The

chatter lessened and her voice resonated with a hint of echo. As she moved the airborne

microphones followed. Charlie pulled away and kept a discreet distance. When

she wanted him, he would be close at hand. He noticed something on the floor

and picked it up. It was the bullet from the derringer. He’d soon discover if

it really had come from the past.

‘Were the images functioning

independently, or were you in command?’ A voice barracked from the back of the

emporium. Beams of light shifted but the speaker had vanished.

‘Nevertheless,’

Steingarten replied, ‘there were minor glitches,’ she admitted, but that was to

be expected. ‘Columbus hardly reached America without a broken sail or two.’ Steingarten cut a fine line between being

humorous or serious. Some people laughed, most did not dare.

The social engineering was

underway and fully operational. ‘History was about to be reshaped,’ she

declaimed.

The Professor swooped

down towards Lady Steingarten. Behind him the Nubian held out a platter with a

long-haired brown caterpillar on it. Facing Steingarten, Mogadishu leered, squeezed

the caterpillar and plopped it into his mouth. ‘Steingarten could never swallow

a poisonous caterpillar,’ the albino whispered to the Nubian and winked.

Microphones sped from

all corners of the auditorium to place themselves at the disposal of the

foremost figures present. Charlie manoeuvred himself behind Steingarten, but

not too close. His thumb was hooked into his belt as if he would reach into his

trousers at a moment’s notice. It was a strange posture to assume, but Charlie

often did things like that. However, no one noticed the ineffectual Charlie do anything.

His innocuous presence made him perfect spy material, a virtue Steingarten had

in the past benefited from.

‘I must inform you,’ Mogadishu

began with an eye on the nearest microphone. Steingarten interrupted; ‘a

biblical plague. a punishment for breaking the 11th commandment.’

Mogadishu gawped at

Steingarten, who appeared to have read his thoughts. ‘I have not read your thoughts. That’s facile

thinking,’ Steingarten sighed. Mogadishu gasped; was she about to strangle him

there and then, in front of everyone? Could his muscular Nubian, Charlemagne

prevent anything?

‘It’ll take more than a

marching bed of inedible caterpillars to stop progress into the past to redeem

the future. So your pigment deprivation is protective, well bully for you,’ Steingarten

snarled, gnashing her teeth almost in his face. ‘You’re too late and it’ll take

more than a plateful of worms to impress.’

Charlie led the

approving outburst, and no one was slow to follow.

Mogadishu gave

Charlemagne a withering look: Why had he not known she was a step ahead. He was

tempted to slap Charlemagne for dereliction of duty, and worse than that, for

being stupid and not knowing. What a pathetic lover he had acquired, Mogadishu whimpered.

Steingarten thrust two

fingers between her lips, whistled and waving the microphones aside said

quietly to Mogadishu, ‘you stupid prick be careful; if the caterpillar can’t

kill you, I might.’ Steingarten slapped the armrest panel and sent the ivory chair

spinning away.

Cloistered in close

proximity with no evident means of restraint a vanguard of thick-skinned

predators paraded across the stage past Steingarten. Charlie scurried behind

her and the audience hurriedly took to their seats. More animals entered behind

scientists in protective suits with helmets bloated with gadgetry. The first

scientist was ensconced in a leather seat attached to the shoulders of a gray

ape. The second scientist straddled a saddle strapped onto a lion. Further

along the meandering column, packed on top of elephants, more scientists in

protective suits followed with long handled brooms. The Steingarten platoons were

en route to confront the approaching army of caterpillars whose poisonous hairs

were lethal.

Additional screens dropped

from the ceiling charting the animal’s progress en route to the ground above and

the earth mound encompassing the Steingarten Foundation.

An air-driven platform,

a ‘floater’ drew alongside Lady Steingarten. She stepped onto it and clutched a

rail, scooping up the dangling straps and buckled on a leather waist harness.

Charlie clenched his teeth as a leopard loped

past almost touching him. He prayed to any god within hearing distance to stop

him from fainting, and closed his eyes.

Lady Steingarten squeezed

the side of the rail. The floater tilted and swept towards Charlie. She held

out a metal bracket which snapped shut around his midriff and she jerked him

onto the floater tearing his shirt and lacerating his chest.

Pressed against Lady Steingarten Charlie clung

on for dear life as the floater lifted and stopped in front of the largest screen.

Charlie scrambled into the second set of straps and secured himself.

Steingarten began to sway dancing to a distant sound. Animal noises drifted out

of the audio system, drawing nearer and growing louder.

Blood seeped through the

remnants of Charlie’s shirt. He felt he must look a sight. Charlie did not like

that. Steingarten’s gyrations coalesced with the rumblings from the animals

flickering on the screens. Steingarten thrust a hand forward. Onscreen a herd

of wildebeest swooped through the British Museum Central Court leaving their prints

in the sand and dust accumulated over a thousand years.

Steingarten scratched

at the air and the animal roars resounded through the emporium. Above ground the

animals stampeded out the entrances at the base of the mound. They drew to a

halt and milled about.

The scientists dismounted

and assembled to the rear of the animals closing ranks and advancing. In the

sunlit distance waves of green swerved to meet the animals. The first pack wild

dogs disappeared into the green deluge gnashing them to shreds. The elephants

impervious to the caterpillars stamped through and the Wildebeest encircled the

caterpillar like trail drivers herding cattle.

Steingarten, dripping

with sweat, waved her arms slowly. The audience believed she had orchestrated the

animals. The caterpillars were crushed and driven into circles, compelled to

turn, unable to break out, nibbling every speck of grass, weed or plant in

their path until the ground was barren. The cannibalism of the green worms

began. Those in the lead fell into the jaws of those behind until no living

caterpillar was left. Clouds of grit with flecks of hairy green covered the

ground for miles.

In the settling dust,

lines of scientists in protective clothing swept the caterpillar detritus into

piles and set fire to them. The animals gathered at the entrances of the mound

but when the scientists headed back underground the animals did not follow them.

They moved away in different directions, as Steingarten had calculated.

*

Charlie’s tattered

shirt flapped as they glided over the Thames snaking between rundown tower

blocks and Georgian squares encircled by Victorian terraces. Squatters in parks

were building fires. Blocks of high rise buildings spilt over with garbage and

people. Steingarten was struck by how London had deteriorated. The once crowded

skyline was desolate and the streets empty. Abandoned cars lay on their sides,

burnt out husks. They coasted over a park surrounded by razor wire and patrolled

by armed guards. Picnickers toasted Steingarten with the popping of champagne

corks. Bursts of loud music marked their passing disregarding the noise

abatement regulations.

Steingarten swerved across

a dimly lit hillside. Stones catapulted against the underside of the floater. Steingarten

told Charlie things looked worse than she had imagined and Charlie wondered

where she had been hiding, and where were they going. Steingarten reached back

and stroked his crotch as they rose opposite the top of a tall building; a fortress

haven for those who could afford it, and the Foundation could afford anything.

A pair of sliding glass

doors opened and they coasted inside. The floater stopped in midair. Steingarten

stepped down, lifted Charlie and lowered him to the carpet. Charlie exhaled as

his shoes sunk into the thick pile. It was many years since he’d last felt such

luxury.

A team of decorators

and technicians were putting finishing touches to the refurbishing. A few of

them stared with disbelief on recognising Steingarten. ‘I am not a ghost,’ she

announced curtly.

Silently, obsequiously,

the work team squeezed onto the floater. Steingarten watched them suspiciously

as the floater went off and pressed a code into her wristband. Charlie gasped

as the floater tilted. ‘Please don’t,’ he pleaded, touching her on the elbow. She

moved her hand away from the control. The floater righted itself and sped away.

It was a reminder to Charlie that his great love was still the same person.

The glass doors slid

shut. Lady Steingarten picked Charlie up, lowered him onto a floating sofa, and

flung a package at him; inside were laundered shirts. She slid past a row of

monitors and control panels, switching and adjusting some by hand, others with

a fleeting gesture. Charlie rolled onto his side and gazed at vases stuffed with

exotic stems starting to blossom. He could smell the scent and wondered if it

was artificial. Soft lighting pulsated like a breathing entity, attuned to

Steingarten’s heartbeat. Steingarten removed Charlie’s boots and unbuckled his

trousers. She was about to say something but decided Charlie was the least of

her worries as she reached into his trousers. Charlie opened his arms.

Dressed and showered as

post coital decorum advocated in the 4th millennium, they lay in

each other’s arms satiated; pleased it was sans medicinal aids or stimulants.

Both woke with a start. Steingarten rolled

onto her stomach staring at the wall opposite. In its centre a glimmer of light

was expanding in tandem with sounds drawing closer. Quietly she asked if Charlie

had touched anything. He shook his head and reached into his crumpled trousers.

He extricated a facsimile magnum with a hexagonal barrel.

A disembodied voice

with a slow drawl boomed that it was coming for the Lady. Charlie shoved

Steingarten, knocking her off the sofa, and blasted a stream of high velocity projectiles

at the emerging image. The stagecoach burst out of the wall as the projectiles

exploded in rapid succession.

When the debris had

settled and the smoke cleared all that remained was a gaping hole where the

wall had been. Lights blazed in from outside. An airship swept past and a high

tensile plasticized skein sealed the gap onto which reinforced cement was

sprayed. Charlie reloaded the magnum.

The glass doors opened

and an official stepped off a floater accompanied by a team in opaque over-suits.

The official demanded access to the computers and Steingarten threatened to

throw him out. The official gasped, ‘I didn’t know it was you,’ saluted and

withdrew.

Mogadishu appeared in a

midair hologram. He told Steingarten that her experiment was as potent as any

scientific innovation ever conceived but she had overreached herself and could

fall victim to the past. However, with his Nubian necromancer and their arcane

knowledge they could summon power undreamed of. In collaboration they could

reconstruct the past with minimal residual feedback.

The prospect of any

collaboration with Mogadishu and Charlemagne appalled Steingarten and Charlie

equally but neither said a word.

* * *

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)